Documentary filmmaking is a powerful and vital element to our society, and those who are responsible for bringing real stories and issues to a creative medium often have an uncanny ability to make a deep connection to us with their art. Legendary directors and cinematographers such as the Maysles brothers, D.A. Pennabaker & Chris Hegedus, Errol Morris, or Ken Burns have vividly made their marks in recent decades and continue to inspire those who enter the field. Inexpensive video camera equipment and video editing software have helped fuel a new wave of truth-tellers, bringing the tools of the craft within reach of amateurs and students, as well as independent journalists and filmmakers on a budget. Narration is a distinct innovation of the expositional mode of documentary.

Initially manifesting as an omnipresent, omniscient, and objective voice intoned over footage, narration holds the weight of explaining and arguing a film's rhetorical content. Where documentary in the poetic mode thrived on a filmmaker's aesthetic and subjective visual interpretation of a subject, expositional mode collects footage that functions to strengthen the spoken narrative. Film features, news stories, and various television programs lean heavily on its utility as a device for transferring information. Documentary is a wonderful way of showing people an aspect of reality and actuality.

Often used to inform and to share knowledge with their audience, documentaries do not appear to have any boundaries therefore as humans continue to discover, create and explore it is clear that documentary filmmaking will continue to evolve. There are many different forms of documentary and the varying techniques employed can create exceedingly different experiences for the audience. Documentaries make up a specific part of the film industry, within them there are many sub-genres and differing styles.

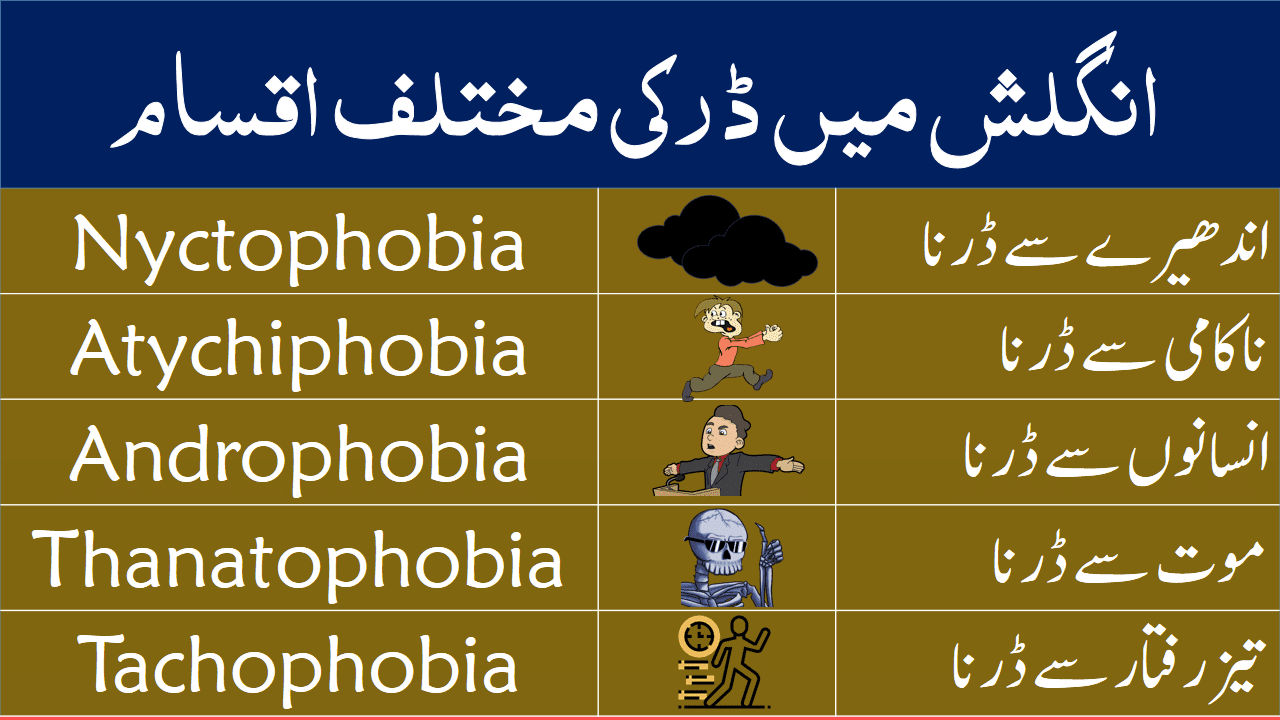

The expository mode is the most familiar of the six types of documentaries. Expository docs are heavily researched and are sometimes referred to as essay films because they aim to educate and explain things — events, issues, ways of life, worlds and exotic settings we know little about. Typical production elements include interviews, illustrative visuals, some actuality, perhaps some graphics and photos and a 'voice of God' narration track. Scripted narration connects the story elements and often unpacks a thesis or an argument. This new edition of Bill Nichols's bestselling text provides an up-to-date introduction to the most important issues in documentary history and criticism.

Designed for students in any field that makes use of visual evidence and persuasive strategies, Introduction to Documentary identifies the distinguishing qualities of documentary and teaches the viewer how to read documentary film. © 2010 by Bill Nichols 1st edition 2001, 2nd edition 2010 All rights reserved. The second aspect--purpose/point of view/approach--is what the filmmakers are trying to say about the subjects of their film. They record social and cultural phenomena they consider significant in order to inform us about these people, events, places, institutions, and problems.

In so doing, documentary filmmakers intend to increase our understanding of, our interest in, and perhaps our sympathy for their subjects. They may hope that through this means of informal education they will enable us to live our lives a little more fully and intelligently. At any rate, the purpose or approach of the makers of most documentary films is to record and interpret the actuality in front of' the camera and microphone in order to inform and/or persuade us to hold some attitude or take some action in relation to their subjects. Documentary is one of three basic creative modes in film, the other two being narrative fiction and experimental avant-garde. Narrative fiction we know as the feature-length entertainment films we see in theaters on a Friday night or on our TV screens; they grow out of literary and theatrical traditions. Experimental or avant-garde films are usually shorts, shown in nontheatrical film societies or series on campuses and in museums; usually they are the work of individual filmmakers and grow out of the tradition of the visual arts.

One approach to the theory, technique, and history of the documentary film might be to describe what the films generally called documentaries have in common, and the ways in which they differ from other types of film. Another possible approach would be to consider how documentary filmmakers define the kinds of films they make. Poetic documentaries, which first appeared in the 1920's, were a sort of reaction against both the content and the rapidly crystallizing grammar of the early fiction film. The poetic mode moved away from continuity editing and instead organized images of the material world by means of associations and patterns, both in terms of time and space.

Well-rounded characters—'life-like people'—were absent; instead, people appeared in these films as entities, just like any other, that are found in the material world. Their disruption of the coherence of time and space—a coherence favored by the fiction films of the day—can also be seen as an element of the modernist counter-model of cinematic narrative. The 'real world'—Nichols calls it the "historical world"—was broken up into fragments and aesthetically reconstituted using film form. The Observational mode, also referred to as cinema verité, direct cinema or fly-on-the-wall documentary is a more specific type of documentary telling.

Observational documentaries were essentially born out of a movement in the 1960s and 1970s by a group of filmmakers who referred to themselves as 'actuality filmmakers'. Due to the advance in technology during this time, sound and camera equipment became easier to use and manoeuvre . This allowed filmmakers more freedom and the ability to observe events without being intrusive to their subjects. The concept of direct cinema is that the best way to see truth is to view it without any involvement or influence.

There are of course arguments asking how natural someone can be when a camera is present, despite how non-intrusive it is. VJ/DJ technology includes hardware and software that can be used to playback video/audio loops, as well as render real time effects, such as slow motion, reverse playback, mirror imaging, colour effects and so on. It is also possible to re-time video loops so that they playback in time with the beats per minute of any given tune that is playing, by pre-programming the video samplers, or VJ software. As such, it is possible to edit video sequences on the fly that are in synch with the rhythm of the soundtrack.

This is fairly standard VJ practice; however it is the use of actuality footage that makes the link between VJ/DJ culture and documentary film. Hardware and software can also be pre-programmed to sequence sounds and images in a random, automated fashion. For example, let's say there is an electronic track playing at 120 beats per minute, video loops can be programmed so that they play back in time with the music.

This is especially effective when using footage of dancers, who will appear to be dancing in time with the music. The hardware/software can also be programmed to cut between images in time with the end of, say, a four-bar musical sequence. A documentary film director may adopt the so-called "observational" mode of filming or try to be like "a fly on the wall" - but this is a process demanding a lot of choices both in the recording and in the editing phase. It is not just about recording what is there; it is also about selecting and presenting and editing in such a way that we see present conditions as wrong and begin to look for alternatives that should be brought about. Documentary film- making - and also the reception of documentary films - is all about ethics, politics and an aesthetic approach, and as such it is a highly subjective or personal matter, it is now argued. The documentary, a genre as old as cinema itself, has traditionally aspired to objectivity.

Whether making ethnographic, propagandistic, or educational films, documentarians have pointed the camera outward, drawing as little attention to themselves as possible. In recent decades, however, a new kind of documentary has emerged in which the filmmaker has become the subject of the work. Whether chronicling family history, sexual identity, or a personal or social world, this new generation of nonfiction filmmakers has defiantly embraced autobiography. In The Subject of Documentary, Michael Renov focuses on how documentary filmmaking has become an important means for both examining and constructing selfhood. The nature of documentary films has expanded in the past 20 years from the cinema verité style introduced in the 1960s in which the use of portable camera and sound equipment allowed an intimate relationship between filmmaker and subject. The line blurs between documentary and narrative and some works are very personal, such as Marlon Riggs's Tongues Untied and Black Is...Black Ain't , which mix expressive, poetic, and rhetorical elements and stresses subjectivities rather than historical materials.

Among the various definitions of documentary, one offered by Raymond Spottiswoode in A Grammar of the Film, first published in 1935, seems to me among the most adequate; certainly it applies quite satisfactorily to documentaries of the 1930s. Spottiswoode does not acknowledge as part of documentary the filmmakers' social purposes or their concern with the effects of their films on audiences. He was subsequently hired by Grierson at the General Post Office Film Unit as a "tea boy"--a general assistant, what we could call a gopher ("go for" this and that). According to a popular anecdote, when Grierson read A Grammar of the Film he decided that Spottiswoode had better remain in that humble position a while longer.

Grierson regarded the purposes and effects of films of ultimate importance. Third, the form of a film is the formative process, including the filmmakers' original conception, the sights and sounds selected for use, and the structures into which they are fitted. Documentaries, whether scripted in advance or confined to recorded spontaneous action, are derived from and limited to actuality. Documentary filmmakers confine themselves to extracting and arranging from what already exists rather than making up content. They may recreate what they have observed but they do not create totally out of' imagination as creators of stories can do. Though documentarians may follow a chronological line and include people in their films, they do not employ plot or character development as standard means of organization as do fiction filmmakers.

The form of a documentary is mainly determined by subject, purpose, and approach. Usually there is no conventional dramaturgical progression from exposition to complication to discovery to climax to denouement. Documentary forms tend to be functional, varied and looser than those of short stories, novels, or plays. They are more like non-narrative literary forms, such as essays, advertisements, editorials, or poems. Another common type of documentary filmmaking, the participatory mode involves the subject and filmmaker together.

This usually includes interviews, conversations and maybe the exchange of experiences. In this, the filmmaker becomes a character in the film, and thus part of the events that happen. You can see this form in talk shows, witness statements or interviews. In this chapter we argue that certain salient contrasts that Frederick Wiseman presents non-verbally and multimodally in his Direct Cinema documentaries can be understood as antitheses that play an argumentative role. In this type of documentary, which renounces the use of voice-over narration and music, a filmmaker has to rely on cinematography and editing in combination with participants' spoken language to guide viewers' interpretations.

We focus on instances of visual and multimodal antithesis in five of Wiseman's early films and one later film . Finding the theoretical space where cinema and philosophy meet, Malin Wahlberg's sophisticated approach to the experience of documentary film aligns with attempts to reconsider the premises of existential phenomenology. All the types of documentaries have their own distinguishing characteristics. For example, it can be argued that Michael Moore's films straddle both participatory and performative modes. Additionally, masters of direct cinema Albert and David Maysles were clearly operating in participatory as well as in observational mode. They were not afraid to include in their films off topic interactions between crew and subject.

Reflexive documentaries acknowledge the way a documentary is constructed and that it is impossible to show a purely objective and truthful subject due to how many processes there are. From the use of the camera to the editing and the filmmaker themselves, there will always be subjectivity or decisions that need to be made which will change the story, whether it be intentional or not. As Bill Nichols wrote, the reflexive mode will provoke audiences to "question the authenticity of documentary in general". Mocumentaries can sometimes fall under the reflexive mode due to their self-awareness. The observational mode emerged in reaction to the expository mode and to technology changes. Cameras became lighter and quieter, lenses became faster and more sensitive to low light, and sound recording went wireless.

These equipment changes allowed smaller-sized crews, which could gain access to more intimate spaces and more spontaneous moments. Ultimately, observational documentary filmmakers sought to let life unfold before their cameras without their interference. Instead of filmmaking methods, other documentarians have centered their definitions around the purposes, functions, and effects of documentary. Indeed, Rotha did not exclude the use of actors and studios from documentary as long as the filmmaker's purpose was to help a society function better, to contribute to more satisfying lives for its people. The continuous mechanical recording of a raw tape lacks the touch of someone selecting and editing for the purpose of expressing or communicating something to someone.

Both fiction and non-fiction films differ markedly from a simple mirroring or duplicative function. Time may be condensed and the chronology changed, music, subtitles, or voice-over added, shots may be interlaced or interrupted by wipes, etc. As a rule of thumb, a film is hardly a film without camera work, cuts or editing, and it is neither a fiction film nor a documentary if it is nothing more than a "re-presentation" of what happened to be in front of a lens and a microphone. Observational documentaries attempt to simply and spontaneously observe lived life with a minimum of intervention.

Filmmakers who worked in this subgenre often saw the poetic mode as too abstract and the expository mode as too didactic. The first observational docs date back to the 1960s; the technological developments which made them possible include mobile lightweight cameras and portable sound recording equipment for synchronized sound. Often, this mode of film eschewed voice-over commentary, post-synchronized dialogue and music, or re-enactments. The films aimed for immediacy, intimacy, and revelation of individual human character in ordinary life situations.

Filmmakers who worked in this sub-genre often saw the poetic mode as too abstract and the expository mode as too didactic. The first observational docs date back to the 1960's; the technological developments which made them possible include mobile lighweight cameras and portable sound recording equipment for synchronized sound. The film in which the filmmaker is the most prominent is Headbanger's Journey. It follows Dunn, he is on camera, the story is narrated by him, he interviews the subjects himself, and he is heavily involved with them. Compared to Dunn, Spheeris's presence in The Decline of Western Civilization and especially Bendjelloul's presence in Searching for Sugar Man are much less prominent. Nevertheless, the directors' involvements with their subjects and their actions place these three films in participatory mode.

In Lot 63, Grave C, Green appears on camera momentarily, holding a microphone to interview Wilkes. Even his brief presence is enough to keep the film in the field of documentary. Crossing the Bridge, on the other hand, with the total absence of the filmmaker, and with its style that narrates the film through Hacke, a subject—almost a fictional character—blurs the boundaries between documentary and fiction. Hacke interacts with the subjects and he even plays songs with some of them. The strength of Lot 63, Grave C comes not from the choice of plot or the story, but from the way Green presents it.

He follows Edward Wilkes, the general manager of Skyview Memorial Lawn, the cemetery where Hunter's grave is located, and tells about Hunter through Wilkes's words. Instead of interviewing Wilkes in front of the camera, Green constructs his way of storytelling by following Wilkes as he walks from the entrance gate of the cemetery to Hunter's grave. During this walk, Green uses Wilkes's voice mostly off-screen, but in some instances he also shows Wilkes talking. The film is almost ten minutes in length, and nearly five minutes of it include shots of Wilkes walking and standing, and other cemetery scenes on Wilkes's way from the gate to Hunter's grave. Green also uses intertitles to give brief information about the Altamont Speedway Free Concert and the incident that happened that day.

The film includes footage of Hunter's stabbing from Gimme Shelter and shots of newspaper clippings on microfilm. 18In this sense, any significance found within the sonic track is purely a matter of interpretation for the listener to decode their own meanings. Cox and I were not intent on attempting to attach any kind of specific symbolic significance to the sounds used; rather the individual sounds were orchestrated in ways that made musical sense, rather than trying to encode specific meanings.

Ultimately we wanted the audience to find pleasure in the soundtrack in order to find it interesting and enjoyable in its own right. Once the banal everyday images have been re-contextualized through filmic devices, then audiences arguably have a greater opportunity to marvel at the world around them, achieved through a cinematic re-seeing and re-hearing of that world. Performative documentaries stress subjective experience and emotional response to the world. This subgenre might also lend itself to certain groups (e.g. women, ethnic minorities, gays and lesbians, etc.) to "speak about themselves".

Often, a battery of techniques, many borrowed from fiction or avant-garde films, are used. Performative docs often link up personal accounts or experiences with larger political or historical realities. The release of The Act of Killing directed by Joshua Oppenheimer has introduced possibilities for emerging forms of the hybrid documentary. Traditional documentary filmmaking typically removes signs of fictionalization to distinguish itself from fictional film genres. Audiences have recently become more distrustful of the media's traditional fact production, making them more receptive to experimental ways of telling facts.

The hybrid documentary implements truth games to challenge traditional fact production. Although it is fact-based, the hybrid documentary is not explicit about what should be understood, creating an open dialogue between subject and audience. Clio Barnard's The Arbor , Joshua Oppenheimer's The Act of Killing , Mads Brügger's The Ambassador, and Alma Har'el's Bombay Beach are a few notable examples. This sub-genre might also lend itself to certain groups (e.g. women, ethnic minorities, gays and lesbians, etc) to 'speak about themselves.' Often, a battery of techniques, many borrowed from fiction or avant-garde films, are used. Performative documentaries will emphasize and encourage the filmmakers involvement with the subject. Performative documentaries tend to be more emotionally driven and may have a larger political or historical motivation.

Because the filmmaker tends to be passionately involved, performative documentaries will usually be subjective in one way or another. Unlike many modes of documentary, performative do not set out to reach a truth but show a perspective or 'what is like to be there'. As mentioned earlier, a documentary film is a kind of film that presents reality. It was previously known as "actuality films" and runs for only one minute or less. Today, documentary films have evolved to be longer in run time and have more categories.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.